Incentivizing better journalism

Facilitating truth-finding through prediction markets

The future of journalism is in flux. Traditional media outlets (e.g. the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal) are struggling to maintain their legacy status as the gold standards of journalism. Meanwhile, many believe that the future of coverage is on platforms like Twitter – where real time news isn’t inhibited by an editor, expertise is distributed, there’s little to no censoring, and no bureaucracy facilitates what gets published.

I’ll acknowledge my bias – for the subjects I follow, traditional media doesn’t offer high-quality coverage. The bankruptcy of FTX, a widely used cryptocurrency exchange (that I praised a few posts ago), was chronicled in real-time on Twitter. Even now, traditional media coverage of the founder Sam Bankman-Fried seems soft, refusing to call him out for clear fraud (he was a heavy donor to most platforms). More importantly, if the New York Times started filling articles with the intricacies of liquidation engines, backstop liquidity provision, and delta-neutral market making, they’d alienate the bulk of their mainstream audience. For the more technical subjects, it pays to use expert-to-follower networks like Twitter or Substack.

I’ll also acknowledge the converse – the same characteristics that make Twitter great at breaking real-time news (no editor, fragmented experts, no bureaucracy) actively enable fake news. In short, I believe neither category of platforms offers a sufficient general-purpose tool to deliver high quality news.

1. Structural issues

The inadequacies of both mediums stem from their profit models. In the traditional media world, coverage was less sensational and more robust when people bought a physical paper with multiple stories tailored to different audiences. As news migrated to the digital world, the revenue model changed to pay-per-click (ads). Sensational news attracted the most clicks, translating to more ad revenue. As corporations with obligations to their shareholders, traditional media refocused to prioritize this high-click news. This shift benefitted their bottom line in other ways – it’s expensive to have journalists on the ground reporting breaking stories or digging for nuance. If it’s cheaper and more lucrative to badly repackage easily accessible news, the current state of media is no mystery.

Social media platforms are an interesting system because individual accounts have different incentives from the platform. An individual account posts to maximize its followings and impressions. The social media platform wants to drive traffic to increase ad spend (see a trend?). Ads are the most lucrative when you can selectively show them to the people most likely to buy the good or service advertised. The Nash Equilibrium of this model is the segmentation of users into echo chambers. Here, accounts get more followers, likes, and comments because the algorithm promotes their content to those already likely to agree. Advertisers can isolate ads to uniform groups, increasing conversion rates. The platform rakes in cash. Everyone leaves happy – but the truth gets trampled.

A pay-per-click model is incompatible with accurate reporting because it prioritizes page hits over accuracy. In traditional media, there are no incentives to cover difficult stories and accurately represent shades of grey. And, to be frank, no one goes to social media platforms to have their opinion challenged – appealing to echo chambers and quality journalism are mutually exclusive.

Consumers who want to seek out high-quality or objective news struggle to find that coverage across subjects. Experts are fragmented, especially in niche industries. Consequently, there is no single platform reporting all breaking news about a particular topic without an ideological bent or framing.

2. Alternative models

Where, if anywhere, does journalism work best? One category of investigative journalists that consistently produce novel, nuanced, and high-quality research are hedge funds, and specifically, short sellers. Usually, short sellers will spend months to years researching a specific company that they feel is overvalued. They’ll accumulate damning evidence of deception, fraud, or malpractice from primary sources using replicable methods. If they feel they have compelling evidence on a company, they’ll take a short position (borrowing stock, selling it, and promising to buy it back later). They’ll publish this evidence on independent venues. If people agree with their analysis, institutions will start offloading the targeted stocks, leading to profits from the short position.

The second and third-order consequences are admirable. These institutions have exposed fraud, lead to regulation, and prompted the resignation of officials within months. Nathan Anderson, the founder of short seller Hindenburg Research, tried submitting whistleblower complaints to the government before realizing they were 1) slow to act and 2) whistleblowers often aren’t compensated. Leveraging markets offered a better structure.

For example, Snow Lake Capital authored a research report on the Chinese coffee chain Luckin Coffee, which at the time, was backed by investors including Point72 and BlackRock. After performing spot checks on individual stores and tracking sales, Snow Lake Capital realized Luckin was falsifying sales. This boots-on-the-ground diligence was enabled by the financial incentives of a successful short sale.

Hindenburg Research similarly authored an exposé about the EV trucking company Nikola. Evidence of fraud included firsthand text messages with employees, road testing of the location commercials were filmed (proving that the truck was rolling down a hill, not self-propelling), images of hidden wiring at truck exhibits, and a detailed history of Trevor Milton’s propensity for fraud. This research single-handedly ended a $20B farce – Nikola trades around ~$1B market cap today. Where whistleblowing failed, free markets prevailed.

Short sellers’ research doesn’t monetize on engagement or ads – if it’s widely accepted as true, the short positions will profit. For consumers, there are financial incentives to taking it seriously, so people don’t tune out if it’s dense, nuanced, or uninteresting. Most importantly, the author only makes money if their story is accurate. As far as I know, this structure is the most direct way to tie the profit structure of journalism to the accuracy of coverage.

Moreover, short sellers that are consistently correct with their coverage are able to raise more capital from limited partners – analogous to a Twitter account attracting followers for consistently high-quality content. These LPs have their own financial incentives aligned with truthful reporting and the elimination of fraud and deceptive practices. On net, this positive feedback loop creates a better society, especially when the root cause of a short is fraud. The logical extension of this structure is activist funds – buyers that take roles in undervalued companies, publish their shortcomings, clean up management, and profit from appreciate share value. In both cases, markets offer guardrails to facilitate uncovering fraud (short sellers like Scion Capital or Hindenburg Research) and streamlining existing organizations (activist funds like Icahn Enterprises or Pershing Square).

In its current state, this profit model for journalism isn’t scalable. For one, a small minority of coverage-worthy issues relate to publicly traded companies. There aren’t accessible ways to short a private company like FTX, a politician’s reelection campaign, or the internal conduct of the US government. The incentives utilized by hedge funds might incentivize accurate journalism, but they only seem applicable to a small niche of coverage-worthy stories. However, finding ways to reinvent market incentives for different subjects might positively effect journalism.

3. The role of prediction markets

Prediction markets can create a market structure for events that don’t normally have publicly traded components. A prerequisite to understanding how a prediction market could facilitate better journalism is defining a prediction market:

What is an information market? (from Polymarket Docs)

An information market is where people buy and sell shares on how a future event will resolve. Prices change in response to trading activity. You can buy, trade, or sell shares in future outcomes.

Who sets the probabilities on a market?

The prices of shares in each market reflect the probabilities of the outcomes. Shares are valued between $0.00 and $1.00 and prices change depending on traders’ collective beliefs on the likelihood of the market resolving in either direction. For instance, if the price for a “Yes” share is $0.75, then the market believes the probability that the event will occur is 75%.

What are the different types of markets?

There are 3 types of markets that currently exist:

Binary - A market with two options that will resolve either $1 or $0. (ex: Will Tetranode have over 100k Twitter followers by 12/31/2025? YES/NO)

Categorical - A market with multiple options that will resolve either $1 or $0. (ex: What ice cream will have the most sales in 2025? Chocolate/Vanilla/Strawberry/Other)

Scalar - A market that resolves to where the final value sits between a lower and upper bound.

What will the population of Spain be in their upcoming census (47M-55M)? Long/Short)

If the population is 50M, the outcomes will resolve to: Long = $0.375 & Short = $0.625

A prediction market can be built around any publicly verifiable outcome. Already, Polymarket trades outcomes from the winners of national elections to esoteric business events like the chance of private companies filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. This information is incredibly accurate – Kalshi outlines ways to use their prediction markets to forecast events.

Experts already take substantive positions in these markets – this “informed flow” is one of the reasons that prediction markets can predict events with such accuracy. In the status quo, it’s abnormal for experts who’ve taken large positions in prediction markets to justify their reasoning. A prediction-market based news platform would change that. Consider how short sellers operate:

Conduct in-depth research on a company to generate alpha

Take a short position in the company

Publish in-depth research

If markets agree, the short position will be profitable

With prediction market, any expert can follow a similar flow:

Identify a mispriced event

Take a direction in the market

Publish their research

If markets (i.e. other participants) agree, the prediction market will move closer to equilibrium value. The expert can close their position immediately and profit, or wait until the event resolves to 0 or 1 to profit.

In this case, both an experts’ research and position in a market is publicly available, aligning incentives. The expert posting research only makes money if they are correct. The size of their position signals their conviction in how mispriced a market is, so audiences know they have skin in the game and aren’t just posturing (which a lot of “experts” frequently do on cable news panels). The market will resolve in a publicly verifiable way, mitigating the risk of market manipulation.

If someone posting research exits their position early, it represents a lack of conviction in their research or an attempt to misprice markets in the short term. There’s little to no penalty for inaccurate information on social networks or mainstream media (the former has too much content to police and the latter is notorious for adding “reportedly” to shirk liability), but if someone actively causes people to lose money in a prediction market, there’s a good chance that they also lose credibility and their following. Over the long term, the prediction market based news platform will converge to offer 1) accurate data about events and 2) a network of experts with a track record of delivering genuine insights about issues. News media, followers, and the platform will be united in pursuit of profit.

The self-correcting nature of markets mean that this news platform is intrinsically antifragile, even without active moderation.

4. A redesigned news platform leveraging Polymarket

To aggregate vague ideas about news, information accuracy, and incentives, it might be helpful to walk through a potential news platform built on top of Polymarket: a general purpose prediction market built on Polygon covering a variety of events based on a constant-product AMM.

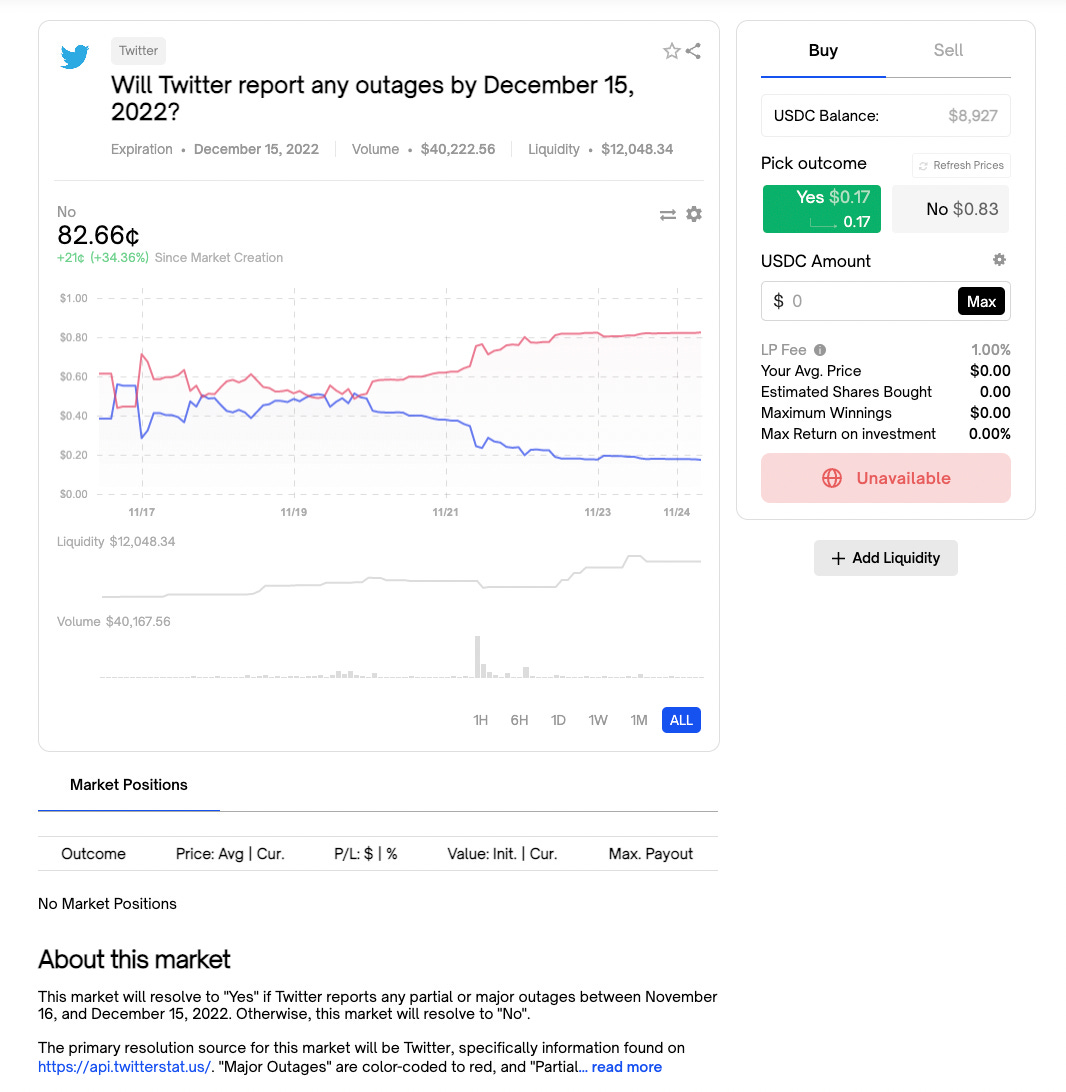

I’ll walk through an example using an ongoing prediction market about whether Twitter will experience a major outage. I feel this example is illustrative because 1) Twitter is no longer publicly traded, 2) media coverage of Twitter has not been objective, and 3) expert opinions are more valuable than empty speculation, but experts currently have no incentive to offer detailed warrants.

Let’s call our made-up news platform built on top of Polymarket the News Exchange (NX). The news exchange might have threads to discuss each market (similar to Reddit threads). The underlying market would exist on Polymarket, and the front-end of NX would offer ways to enter positions and display positions without leaving the platform. The UI/UX might resemble Polymarket:

Note that in the “About this market” section, the outcome is independently verifiable and is not subject to external manipulation.

A user might have an email and a wallet linked to both Polymarket and NX. This would function as their user profile. If they chose, they could doxx themselves by adding their identity and credentials (i.e. works at the WSJ, studied software engineering, worked X previous roles) or remain anonymous (where their posts and positions would be evaluated purely on their independent merits). In both cases, anyone could see their past positions and their P&L, which is a proxy for user accuracy.

NX would attract a variety of people to take positions – from traditional media platforms like the NYT to niche sector experts looking to share knowledge and simultaneously make money. I anticipate many passive followers being anyone wanting accurate information about the world.

Let’s say that an expert recognized Twitter performance slowing down, and believed this was a precursor to a platform outage. They might publish a post on NX in the thread discussing this market. They might point out ways to measure Twitter’s performance, benchmark metrics of other social media platforms, and a trend graph of Twitter’s performance. They might include that they used to be backend engineers at other high-throughput startups. Before posting to the forum, they would be prompted to take a position in the prediction market by entering the amount they wanted to bet and the probability of an outage that they found reasonable.

Liquidity in an AMM-based prediction market is a challenge. Without sufficient liquidity, experts cannot make large-cap predictions without shifting the market. If there is excess liquidity in a market with little volume, capital is not being used efficiently. One solution is similar just-in-time liquidity, a MEV strategy originating Uniswap V3. When an order is routed through NX, they can calculate the requisite liquidity required to reach a position’s target size and the target price as defined by the person taking a position. Through this structure, NX’s makes money on the 1% LP fee that Polymarket offers market makers (in practice, <1% of total volume on prediction markets, since there will probably be other LPs). The profit model of NX becomes facilitating back-and-forth discussion on events, which simultaneously makes prediction markets more accurate.

It is always preferable to take a position and post reasoning for it instead of just taking a position in the prediction market. In the former case, person X takes the position and waits for the market to resolve itself. In the latter case, person X takes the exact same position and gives others reasons to piggyback on. This creates a chance for the position to cross the fair value as other people pile in, creating opportunities to exit early. Further, if posting justification for a position is a prerequisite for accessing JIT liquidity, NX offers experts additional incentives to use the platform.

After a position is submitted, a few outcomes are likely:

No one disagrees with the price

This is probably an accurate probability for an event based on currently available information

Other people disagree with the price, and are willing to take competing positions

They take competing positions. The resulting volume is good for the platform and leads to a more accurate price for the event.

If someone has taken a high conviction bet, another competing high conviction bet would be necessary to change the price.

If this can be done without adding additional liquidity, none will be added.

If additional liquidity is necessary, JIT liquidity provisions are once again used.

If the one disagreeing doesn’t have enough capital to reach their target price, passive followers who agree with their stance have an arbitrage opportunity in moving the market to an accurate equilibrium.

This process iterates until there is no dissent or new information becomes available. There is an expectation that newer posts in a thread will interact with past posts by corroborating or refuting them. Posts in a thread for each market would be timestamped, making it clear how the market has changed with each opinion. People’s 1) position entering the market and 2) position currently would be tracked on the thread. NX would be immutable, preventing deception through edits. If a NYT author made apocalyptic claims about Twitter but refused to take a position predicting a platform outage, users have the tools to independently classify that prediction as hot air. The possibility of profit opportunities keeps passive listeners tuned in.

If someone posts an exaggerated claim to move markets, waits for the prediction market to swing, and immediately exits their position, the transparency and immutability of NX means people will immediately associate that account with scammy/deceptive behavior. In the long run, people won’t take their predictions seriously, making their strategy EV-negative. Further, the burden of short sellers is to use publicly verifiable information to make their case – a position without concrete evidence is unlikely to be taken seriously. Similarly, a concern might be new accounts being created to manipulate markets. I believe that new, undoxxed accounts wouldn’t significantly swing markets.

A thread closes and is archived when the underlying market resolves. Information in a thread cannot be edited or removed once posted. A REST API and prebuilt client would let the rest of the world access information from the NX.

In summary: experts taking positions make money off the accuracy of their position. Followers can make money by taking advantage of arbitrage opportunities created while markets are in flux. The platform makes money by facilitating a high volume of back-and-forth trades, where it serves as a liquidity provider. This platform is complementary with Polymarket because it improves the accuracy of prediction markets and offers deeper liquidity to enable more accurate price discovery.

Though I have some ideas for a go-to-market, Polymarket-specific JIT liquidity strategies, and cross-prediction market liquidity aggregation, I feel those are out the scope of an introductory blog.

5. Caveats

A prediction-market integrated news platform effectively converges on the truth based off information available in the public domain. Financial incentives would lead to incredible outcomes as measured by information accuracy, but if events aren’t independently verifiable (e.g. through a Chainlink oracle), markets are subject to manipulation. In general, most events have a publicly verifiable component – even early-stage private companies can be measured on whether they raise a round above $X. Therefore, this doesn’t feel like a major bottleneck. Litigation records are also a source of truth – these could facilitate particularly interesting markets.

This news platform is poorly suited for normative content. There is no underlying market for a normative article arguing “X bill ought to be passed” or “Y social justice issue is important.” However, I feel that if an underlying platform facilitates agreement on facts, there’s a better basis for crafting normative arguments. Consider accurate information the building blocks of opinion pieces, and let other platforms facilitate that opinion-piece distribution.

My instinct is that the separation of normative and positive news is a good thing. It doesn’t seem healthy that MSNBC reports on breaking news and random authors’ opinions, especially because audiences seem to believe a more prestigious platform automatically makes normative arguments true. This feels as misaligned as the era when investment banks’ research publications were linked to their discretionary trading arms. I would rather endorse the brand of journalism practiced by the Thompson Reuters Institute, which focuses exclusively on breaking facts, or the New Yorker, which publishes exclusively opinion pieces.

Insider trading is a challenge in the proposed NX – but across the world, politicians insider trade all the time. In this case, at least insider trading has the positive externality of delivering accurate information to the public.

6. Summary

Wikipedia changed the way we aggregate historical information by crowdsourcing information. Open platforms like Twitter have struggled to predict or follow real-time events accurately. Simultaneously, as traditional media transitions to an advertising model, their journalistic integrity has been called into question. A news model that rewards accuracy over clicks could address both problems.

AMM-based prediction markets are a valuable primitive because leverage three principles that facilitate accurate information:

Experts making predictions should have skin in the game

People should be able to associate others’ reasoning with their position in a prediction market

News shouldn’t be made of superlatives – it should be restructured to reflect an event’s relative probabilities (for both a yes/no and a discrete range)

Using such a platform, it should be possible to find consensus on the kernels of truth that facilitate productive discussions.

About me: I’m an undergrad at UPenn studying statistics and math. I’m interested in markets and market structure as a tool to facilitate productive social outcomes. I took a gap to build VO2, a marketplace where fans could buy shares of athletes’ future cash flow as tokens – we were backed by Techstars and GC, but ultimately, didn’t get SEC approval to issue tokenized securities. Currently, I run some arbitrage strategies between PredictIt, Polymarket, and Kalshi, and I’m an incoming quant trader at Citadel Securities. Learn more at arhamh.com, and feel free to contact me on Twitter @Habib12Arham or at arham.habib@gmail.com.

Best post yet. Few food for thoughts:

(1) Assume NX is built out... it would be cool to consider how might people layer facts / currently trading events to build new markets. Using a no-code solution drag and drop UI/UX would be sick. Not sure if my wording is clear, do you follow this?

(2) Consider how you'd build it out. Is this it's own media platform is it it a white-labelled backend tool that integrates directly into CNN/MSNBC/Fox. Also, does this have to be on chain? Let's talk GTM.

(3) How would you deal with regulatory purview? Aka assume NX becomes huge and starts to seriously disrupt the ability of certain less transparent governments to function. Also, what are people likely not going to be allowed to bet on (I know Kalshi and PolyMarket probably do a fair bit of this in their Terms & Conditions)?

(4) Can the journalist who creates the prediction market fractionally pull out? Aka, 25% upon seeing certain predictions come through? What if events stay in the gray area for long stretches of time?